Culture, Write here, write now

CATCALLING – STREET HARRASMENT

10 June 2022

CATCALLING:”Sexual harassment, predominantly verbal, occurring in the street. The word catcalling names a series of acts (unsolicited compliments, vulgar comments directed at the victim’s body or attitude, whistling and booing from the car, intrusive questions, insults, and even outright insults) which, because they are considered an expression of a sexist and devaluing mentality, constitute a specific type of sexual harassment and street harassment.

CATCALLING:”Sexual harassment, predominantly verbal, occurring in the street. The word catcalling names a series of acts (unsolicited compliments, vulgar comments directed at the victim’s body or attitude, whistling and booing from the car, intrusive questions, insults, and even outright insults) which, because they are considered an expression of a sexist and devaluing mentality, constitute a specific type of sexual harassment and street harassment.

Called like pets. Like those creatures that reply to a specific sound and reward us for giving them attention. The cat purrs to us. Many people criticize the use of the term ‘catcalling’ because they say, it is a feminist invention because they don’t think about the relevant issues, they have to invent something that didn’t exist before. What did not exist? Harassment in a public place, or the word ‘catcalling’ to define it? Or both? Probably both, for them. What’s the problem? That it bothers you that we raise our voices, that we throw who you are right in your face?

The problem is a word, or the truth behind it? There is always something far more important to think about, and others always have to tell us what is important.

Just out of curiosity, there is already a term in Italy that refers to the animal world to indicate the harassment of women in public spaces. It is a term that defines the harasser as a parrot: it is PAPPAGALLISMO (Parrot=Pappagallo) or the ‘behavior of “street parrots”, i.e. of those who, in an insistent and coarse manner, harass women in the street’.

Just out of curiosity, there is already a term in Italy that refers to the animal world to indicate the harassment of women in public spaces. It is a term that defines the harasser as a parrot: it is PAPPAGALLISMO (Parrot=Pappagallo) or the ‘behavior of “street parrots”, i.e. of those who, in an insistent and coarse manner, harass women in the street’.

Both terms refer to sexual harassment that occurs in the street, in public, by strangers. A harassment that unfortunately, not only in the past but also today, is widely regarded as a form of appreciation, of compliment, to which we should also respond by smiling.

What is overlooked is that in public space there are unwritten rules of behaviour, and one of them concerns a widespread indifference, and lack of intimate and long lasting contact that makes us, for example, engage in conversations with strangers. Although it is considered rather strange that we stop in the street to talk to strangers and engage in any conversation with them, we find ourselves being judged exaggerated if a man in the street shouts to us ‘hey beautiful, looking for company? I would not be judged normal if I stopped people on the street to make comments about their physical appearance or what they were wearing. But as women we have to accept this as a compliment, and not resent it, lest the ‘compliment’ turn into an insult or assault.

When we give someone a compliment, our goal is to make them feel good, right? So we would never do or say anything that would make him/her feel uncomfortable. Before we pay a compliment, we make sure that the person we are paying it to considers it a compliment, right? So let’s end this pantomime of harassment dressed up as a compliment.

Street harassment restricts our freedom to be in public spaces, is a serious form of gender-based violence that sometimes leads to stalking, and is often frightening to be in public places, especially since it is accompanied by a general indifference supported by the idea that it is, if not compliments, at least borderline not very polite attention. It is one of the worst forms of sexism because it is based on the idea that you can say anything you want to a woman, anywhere, at any time. We often feel as we have to modify our behavior in order not to incur harassment, assuming that there is no solution to it.

“Smile!” is the response in case we feel so displaced or vulnerable that we might react to a violation of our being in public, in case we react at all. And we rarely get an immediate reaction, the reasons are many, and knowing the dynamics of violence and harassment does not make us invulnerable. Because it is not our problem, it is a society’s issue as we are considered to be naturally predisposed to exist for the pleasure and consideration of men: and in fact, every woman desires to crown her dream of love with a man who whistles at her in the street or gropes her in public, how can we deny it?

So, if we don’t feel flattered by the harassment disguised as an advance or witty banter, we are unsatisfied, angry women, not very socially inclined, humorless, sexually repressed, and I could go on and on, but I invite you to do so in the comments, recounting your experiences, and sharing the reactions you have had or would like to have had because we can react together and feel safe.

A lot has been said about sexual harassment in public, witnesses have been gathered, social experiments have been carried out, documents have been written and hard work has been done to get it identified as a crime, to have its importance in terms of psychological consequences recognized. Who among us has not had similar experiences? Who has not experienced them in everyday life? Who has not felt discomfort or guilt for having in some way caused harassment? On the other hand, if we live in a world that socially stigmatizes the raped woman who – is too libertine, provocative, young, beautiful, drunk, or drugged – before the rapist, we cannot be surprised at all by the widespread indifference to the subject of street harassment, and it is perhaps for this reason that we find it difficult to share its most intimate aspects. Sometimes it is difficult to explain a discomfort in words, and it is only by condemning the idea that this has anything to do with a compliment that we will be able to talk about an experience that I am sure every one of us is familiar with.

We often engage in conversations about the weather with men whose names we barely know, who continually make sexual allusions, comments, and remarks that exactly show the dimension in which they place every woman: a sexual object, into whose intimacy they can enter when and how they want as if in reply we should be grateful for this attention. It happens. All the time. It also happened to me some time ago: from a routine neighborhood conversation, within the space of two or three sentences, none of which were sexually allusive or hinted at my willingness to have sexual conversations, I found myself receiving an invitation that the poor egocentric man described as ‘adding spice to the conversations’, i.e., to go swimming in his pool even though I did not have my swimming costume on hand. The little man in question always gave the impression of overestimating himself, but even so, for me, it was like a punch in the face. Gosh, a punch in the face that made me fall to my knees, thinking that I certainly couldn’t let it pass like that. Then I rose and reminded myself that men like him deserve a very well-reasoned, unhurried response….the anger I had towards myself for not responding as I would have liked was now all focused on him, and my response came.

Just think about it, it happens every day, and every day we can make a difference, no one can tell us that we have to smile when our bodies are violated, our freedom to walk the streets, or have relationships with people.

We laugh and smile whenever we want, for whomever we want, if we want: before opening a door people must knock, ask if they can come in and wait for an answer, which is not due, never.

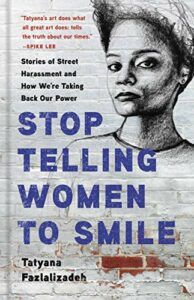

A couple of years ago, in New York, I stumbled upon a book by chance, but as I told you when I enter a bookstore, books stick to my hands! Wandering around Barnes and Noble, my eye fell on the book ‘Stop Telling Women to Smile’ by Tatyana Fazlalizadeh. On the cover, a quote from Spike Lee ‘Tatyana’s art does what all great art does: it tells the truth about our times’.

I turned to the introduction on the first page

I turned to the introduction on the first page

“I was still a girl when my body began to change. When it started to be ogled, stared at, whispered to, touched, followed. No sooner had I begun to understand my own developing body than it began to no longer feel like my own. It felt like a thing. A thing that men wanted. That was when I started to feel uncomfortable, and unsafe. It seemed as thought my body existed for men’s pleasure, and it became something. I was forced to dress myself in for other’s enjoyment”

In a flash I went back over thirty years, those words seemed to be mine. I retraced my life as a girl and then as a woman exactly immersed in that state of discomfort and insecurity, the harassment episodes to which I reacted and those in front of which I was struck dumb. It was about me, it was about all of us.

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh is an American artist, activist, illustrator, painter, street artist: she dedicated several years to understanding the phenomenon of street harassment, i.e. sexual harassment in public places, in the United States, travelling around the country and asking many women to tell their experiences, their definitions of street harassment, their stories. She listened, learned a lot from their stories, and in 2012 decided to embark on a series of street arts that has the title of this book, and which has become a campaign: a series of posters in which she depicts the faces of the women she met and in which she reports what they want to say to their harassers. These posters were put up in public spaces, along public streets, i.e. in places where women suffer harassment.

Through Tatyana’s words, we discover how frequently we are hit by the sexual harassment that comes unexpectedly, everywhere, under the pretense of being welcomed as positive attention, a compliment, an expression of appreciation and irony. And how many times do we deal with the frustration of being left unmoved, or of having given answers that are too incisive not to be called humourless? It happens, every day, everywhere. And Tatyana tells us exactly what it is: harassment received in the street is sexual harassment in a public place. Without consent, without explicitly showing that you want to receive appreciation of your physicality, your clothing, the way you walk and stand in public space. No consent.

Through Tatyana’s words, we discover how frequently we are hit by the sexual harassment that comes unexpectedly, everywhere, under the pretense of being welcomed as positive attention, a compliment, an expression of appreciation and irony. And how many times do we deal with the frustration of being left unmoved, or of having given answers that are too incisive not to be called humourless? It happens, every day, everywhere. And Tatyana tells us exactly what it is: harassment received in the street is sexual harassment in a public place. Without consent, without explicitly showing that you want to receive appreciation of your physicality, your clothing, the way you walk and stand in public space. No consent.

Sometimes I open this book, to remind myself that talking about harassment received in a public space is simply the most natural thing I can do, since no one is asking my permission to violate my freedom of movement: if you just can’t do it, you will be exposed to public ridicule, that’s fine.

The misogynist culture has so much influenced our lives and our thoughts that it is not uncommon to talk to other women about sexual harassment, and to find ourselves facing the devaluing of what is commonly considered to be ‘far more than the violence that women seriously suffer’. So let us try to reflect together, taking our cue from practicing the conflict action that has been transmitted to us through the stories of the women who have accompanied the feminist movement so far – see Gloria Steinem who did not even consider herself a feminist, discovering that she was one through practice and confrontation. Gender-based violence, in all its forms and dynamics, is always violence against women as women, causing physical or psychological suffering, aimed at fixing and maintaining power and control over us, through whatever means. Physical violence is the visible one, femicide is the last act. But before all this, and at the same time, there are all the other forms of violence that we daily experience from men, strangers and not, which the whole of society covers up through justification, the judgment constantly hanging over us, absolution through devaluation of behavior. A man who has no difficulty in harassing a woman in the street, in patting a female reporter who is doing a live sports report, who comes out with phrases such as ‘I’d have that bitch raped by a pack of black men’ as punishment for being disliked, is hopelessly a man who has no other consideration of us than the one that drives all the violence that we are used to considering the only violence against women, that is, beatings…

Not considering catcalling as sexual harassment in a public space opens the door to everything that justifies rape in any other place: if you walk around alone, you can’t expect to be whistled at or called out in the street; then, if you walk around at night, alone, maybe in a miniskirt, even drunk, you might expect to be raped; and again, if you walk around without your husband, show up with other men, go out with girlfriends maybe not married, you might expect him to beat you up. These are not overstatements of reality, this is reality: a reality that concerns all of us, our speeches, our family discussions, what our sons and daughters listen to, what we take into schools, workplaces, café conversations, even into courts, police stations, hospitals. Because in all these places there are people who act in line with their own vision of reality.

Then it is necessary to rewind the tape, to start from the extreme consequences, all the way to harassment in a public place: and to answer those who tell us that there are other problems before catcalling, that catcalling is one of the roots of those problems. And that above all it is we who determine what we consider sexual harassment and what we do not, we do not need someone else to explain it to us. I find it irritating the whole waste of breath of those who think they are expressing an intellectual thought when they assert that feminist battles are others, that catcalling is something we bring up to attract attention when the problems are quite different, going so far as to call it all the result of a victimizing attitude. Disqualifying and criticizing the fight against catcalling means ignoring women’s voices, replacing their voices and experiences, and determining for them exactly what violence, harassment, and a violation of being free to move in public space are. It means forcing them to remain silent because what they feel does not exist. And that is what has happened historically with domestic violence, with rape, with arranged marriages, with child abuse: “if you don’t name it, it doesn’t exist. So shut up, because it’s your whim, if you have a nice ass and they shout it in the street, take it as a compliment, that women have other problems.”. Women…other women, not you. We will always find great experts and experts in our lives and our experiences, in the languages we use, in the struggles we act. Let them speak, we will raise our voices more.