General

LET’S GIVE LIFE…TO DEATH

20 July 2022

“Remember, when you are dead, you do not know you are dead. It is only painful for others.

The same applies when you are stupid.”

– Ricky Gervais –

During my childhood, my parents never avoided talking to me about death. I didn’t grow up in one of those family contexts where children are not made to experience mourning, loss, to preserve them from something that is part of the natural evolution of life, of every life. We are born, we live, we die. I don’t remember asking particular questions about death, but certainly my memory doesn’t reach far enough to remember certain details. The death of my paternal grandfather, which occurred when I was eleven years old, was the first experience of death of a loved one. I remember it all as if it were yesterday because I was not denied to see him dead in the coffin, or even to attend his grave burial. I remember that as we stood in the house waiting for the coffin to be closed, an aunt I had never seen before approached me to say, “but why are you standing here? Why are you crying? You shouldn’t see such things, it’s better to remember him alive, not dead.” I did not fully understand this sentence, besides the fact that asking a person why they mourn someone’s death is symptomatic of a level of stupidity that I later learned, however, was a hallmark of the aunt in question.

Seeing my grandfather dead, going through all the rituals of burial – no funeral was held, per his wishes, and he was not cremated as he would have desired because at the time a written declaration was required, which he had not left – did not in the blink of an eye erase all memories of him alive, it simply made his death tangible: he was gone, and that is what happens to each of us, so why not see with my own eyes such a natural event as death? Of course, it’s an event that leaves deep marks, that has consequences on our lives, it’s not like going to the cinema to see a movie. It’s reality: people die, and we miss them, we feel anger, grief, disbelief, we carry the trauma of some losses with us for years or even our whole lives, we fear death, we hate it because it takes pieces of us away, we need to keep people alive through their celebration, memories, and everything that gives us the feeling that we haven’t let them go.

That’ s all right, I don’ t find anything wrong with that, what I find oppressive — that’ s the expression that recurs every time I talk about it — is the fact that on the one hand we want to keep alive the memory of a person and celebrate their life, and on the other hand we build burial places where there is no space to celebrate that life. And I’m talking in particular about contemporary italian cemeteries, knowing that in other countries there are several different experiences. But, as I always say, we have the “nest” of Catholicism, the Vatican.

We used to go to the cemetery together with my parents, not too often, not on special occasions. My father especially, used to take me to see the monumental graves, those of the partisans, the very old ones, in the oldest part of the cemetery. I, as I moved through this vast space, realized that I was in an immense expanse of concrete and marble-now even larger, resembling in architecture a mixture of a maximum-security prison and a lager, with perimeter turrets-a veritable city of the dead, reproducing the distinctions of living in life: prestigious families own mastodontic chapels with their own entrances, locks, more or less pharaonic arrangements, sometimes busts and statues; the middle class usually gather their dead in multi-family tombs in which each has its own space in the multi-story subdivision, all topped by marble to cover, define, distinguish. ..a condominium in short; then there are the loculi, that is, the proletariat, those who for financial reasons or simply by choice do not stay in condominiums or villas: the loculus is a studio apartment, little larger than the coffin that has to fit into it, set in a large multi-story marble frame, together with other loculi, above ground; finally, the unimitation, that is, burial in a wooden box without zinc lining, in the bare earth. But the latter after ten years are exhumed, and what remains of their bodies are put in a smaller box and transferred to a loculus, to make room for other burials. So, they always end up covered with marble.

My parents would always point out these cultural and class differences to me in our walk through the cemetery. Many people, although from prestigious backgrounds, choose to be interred or end up in the burial grounds or, conversely, many families who are not wealthy make immense sacrifices in order to be able to buy a chapel, to show that they are not part of the masses or because the grief is so great that building a home for their loved one somehow provides more protection, and in visiting them, one has the feeling of going to their home.

Going to the cemetery was not a ritual for us, as it was for many other families-often the same ones who flocked to Church on Sundays-but rather a kind of outing, during which we told pre and post-mortem anecdotes of the people who were no longer with us. Yes, even post-mortem, because my father’s family tomb being a very crowded apartment building – it’s a large and bustling family of mine – every time a body was put down, we would look out to take a count of who was placed where, and the remaining places for those present, who cared so much to be there. Pre-mortem reasoning, after all, they had to secure a roof over their heads, and be all together.

At the cemetery one enters keeping more or less all the same calm attitude, with flowers to be changed, graves to be cleaned – otherwise who knows what people think, that those dead there are not taken care of by anyone, abandoned there as…as…dead, exactly – it is a constant looking around, seeing if someone has brought flowers to the neighbors, if they are fresh, if they are not fake flowers, because the fake flower indicates that one goes rarely to the cemetery! Because the dead must be taken care of, physically I mean, it is not enough to celebrate their memory.

I remember an uncle criticizing my mother because we children did not go often to the cemetery, and that was not respectful. My mother did not mind, she explained that we went to the cemetery if and when we wanted to, because cemetery visits do not measure the love felt. We were lucky, because we were not dragged into the maelstrom of ritual facades that could have been passed down for generations, and that certainly helped me observe some dynamics. And it saved me from that sense of oppression that I felt every time I went there. I had a choice, just as I had had a choice whether to go to church or not, until I was unbaptised in consistency with my beliefs. Some of my friends did not have a choice: they had to go to Church on Sundays, go to the cemetery with their parents every week, receive all the sacraments in the prescribed order and at the prescribed times, and follow the whole path that God and the patriarchy had laid out for them. Then what of it, for the rest of the time in the family they would gossip about anyone, chase away the peddler in offensive tones, avoid all contact with the new foreign neighbors, and pretend not to hear the violence inside the houses they were spying on. All was regular in short. And the strange ones were we who did not go to church and the cemetery….

Growing up, I continued to rarely go to the cemetery, doing so only if I felt the need. Only when my maternal grandmother died – I was in my twenties – did I get into the habit for a while of going to the cemetery once a week to bring her flowers, and I would make the rounds of friends and relatives to leave a flower each. Then I began to feel that sense of oppression again: the marble, the chapels that looked like terraced houses, the thought of all those rotting corpses sealed beneath me and around me…how could I live peacefully with the moment I had chosen to remember the people I loved? How could I sit and spend time there? The cemetery is like the coffee shop: you go, have a coffee and leave. You go, leave flowers, clean up, if you are a believer you make the Sign of the Cross, say a prayer, then go home. What are you doing standing on a marble slab in freezing winter and burning hot summer? With a few exceptions, the cemetery in our cities is lived in silence. No events are held there except institutional memorial ones. One cannot choose how to celebrate the memory of those who are gone if that celebration is considered offensive because it is loud or showy. There is no playing, no singing no dancing in a cemetery, no picnics, no ball games and no games for children, no benches to sit on. You enter by keeping a sober profile and moving slowly, going through this place as if in a parade.

I have experienced many deaths: premature, suicidal, unexpected, suffered, invoked, ignored. And consequently, I have experienced mourning and everything related to remembrance, what oppresses me most of all is the rituality made up of rigid norms, incense, catch phrases, “rest in peace” and “may the earth be light to you” – pity that most of the departed don’t even touch the earth – which these days are wasted on social networks, of priests who liberate from sin and who almost tell us that if you die after so much suffering, you are luckier and closer to God – so what an ass. I am oppressed by the procession to the cemetery, the burial, the low heads and the silences. Not because I find them out of place, but because they are part of a social convention that has nothing to do with the pain of loss. Grief cannot be shackled in ritual, it cannot be homogenized, as every feeling has to do with subjectivity. Commemoration cannot be replaced by the maintenance of the burial site; it deserves more.

My parents constantly remind me that they, as they pass away, don’t want all this stuff, that they want to be cremated, that they don’t want droves of people lining up for condolences.

Rather than an atheist, I call myself “uncaring”: I live my life according to values that I have cultivated through experience, the education I have received, and the people I have met sometimes by luck, sometimes by disgrace. And I will want to end my life with the knowledge that I have left something behind, that I have sown seeds to help improve the lives of other people and this world. I don’t know what will be there after my passing, I guess nothing surprising, but none of us can say, maybe I will have to change my mind and it wouldn’t be the first time. I will be there, and I will find out, as I did exactly with life. That is not to say that in life I will not experience the pain of loss, the lack of the people I have loved. But I don’t want to go through this experience following yet another socially accepted practice, and the idea that death should be locked up in a huge monument that stands there to remind us that we should fear it. Death is certainly transformation, and there is no birth without death. The moment we are born, we have two certainties: that from our first breath, we will never stop breathing to live; and that we will die sooner or later, like every living being.

I find Thich Nhat Hanh’s thoughts and life fascinating in their simplicity. He, himself, who died in January 2022 at the age of 95, did nothing but invite us to live in the present moment, and to experience death as a transformation. He was doing this from his own life experience, beyond religious belief. That is why you will find his quotes in various articles of mine: little pit stops of regeneration and introspection.

In my wanderings wearing the curiosity glasses, I do not deny that I also go to cemeteries, because the relationship with death tells us a lot about any civilization. For a busybody like me, going to cemeteries is like reading a book, which tells us about the history of an entire people and their relationship with the one event, after birth, that certainly unites us all.

Talking about end-of-life for me is natural; I recognize that many people are uncomfortable doing so, sometimes out of a form of superstition, sometimes to avoid dealing with loss and grief. Fortunately for me, my close circle of friends and family are not prejudiced. But what I found surprising is the fact that a dear friend chose to tackle a topic so dear to me and so complex, to research to the point of developing a dissertation on cemeteries and crematorium design. It is not so usual for a young Architecture graduate student to have the insight to tackle a topic so close to us in our daily lives, but which we keep at a distance because it concerns what we fear and deny most of all. The contemporary cemetery, its critical issues, the life lived in a city where it represents, as Andrea Pastore calls it, “a dead place.” Andrea stimulated my curiosity even more, my need to observe, to understand, especially because he approached this complex work with great passion and insight. Gathering experiences from different countries and different cultures, Andrea asked me to send him some information about cemeteries in Bavaria. In researching cemeteries to visit, I found one that particularly caught my attention, and added a note of wonder to my life. So, during one of the many times of the year we spent in Bavaria with my husband and dog, we decided to organize a

SUNDAY EXCURSION TO THE CEMETERY.

SUNDAY EXCURSION TO THE CEMETERY.

So we went to visit Naturfriedhof Schlosswald in Regental Nature Park, which is part of the Bavarian Forest.

I had visited English, Scottish, and Irish cemeteries, where there is no lack of greenery and nature contact. But I had never come across a natural cemetery, in the woods. This natural cemetery was desired by the municipal administration of Nittenau, with the willingness of the von Drechseled family that has been taking care of the forest for centuries; it was inaugurated in 2015. There are administrations that continue to cement and others aware of the need for contact with nature in order to regain the peace and freedom necessary to cope with detachment. The latter represent everything that, for example, in Italy is not contemplated, due to the inability to consider and define innovation processes through the analysis of the social context and the needs of a society that is constantly going through new challenges. And also because of a clientelist culture that invades every aspect of our life, and our death… to be honest, let’s face it. Our cemeteries are gold mines, think for a moment about the costs you will have incurred.

Coming from Nittenau, you go up the hill in the middle of cultivated fields until you reach the cemetery: there are no fences, no gates, no barriers, just the forest, and the various paths.

There is a large forest map, and wooden buildings that are in perfect harmony with the forest profile: the little wooden house with the office, the changing room for the maintenance staff, a small house to protect the recycling containers from incursions by wildlife that roam the forest, an insect hotel. Everything looks perfectly neat, but in a natural way, without lawns, planters, pots. It is nature decorating everything, managing its own maintenance. Continuing on, at the highest point overlooking the cultivated fields that are painted yellow in spring, an open space with two large wooden pagodas and a cross: that is the place where people gather to commemorate, pray, or simply seek peace. The landscape in front and the sounds of nature are a comfort to those who mour.

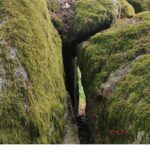

As in any forest, it is okay to go with a dog, because we are walking into a natural place, not a bunker. Before going, we had not explored the cemetery webpage, so walking around we looked to see exactly what the concept of this place was. We began to see glass decorations applied on the trees, or on the ground stones: pictures of nature, animals, landscapes, religious symbols are portrayed on each of them; there were also names and dates of birth and death on some of them. We noticed steel plaques with a QR-code: by framing it, you can see who that tree or stone is assigned to. There is nothing else, no flower pots, candles, puppets, sacred images, marble busts … nothing. there is the birds singing, a few deer standing in distance monitoring movements, surely wild pigs standing at a distance. And nature, which with the changing seasons constantly repaints the landscape, strips and coats trees and rocks with leaves and moss. A few benches here and there, where to sit to read, rest, eat, talk. It is exactly the place where the transformation of our existence takes place: we return to the earth, to nature, to give new life. Exactly there. That oppression felt so many times left me, and I began to build a different relationship with death — with my own death first of all — because I experienced its meaning firsthand. That oppression felt so many times left me, and I began to build a different relationship with death-with my own death first-because I touched its meaning, which recurs in any tongue and reminds us that we finally come back to being

“Asche zur Asche, Staub zum Staube” – in German tongue

“Cenere alla cenere, polvere alla polvere” – in Italian tongue

“ashes to ashes, dust to dust.” – in English tongue

“ashes to ashes, funk to to funky” – in David Bowie’s tongue!

Deceased people’s ashes, stored in natural wooden urns, are buried under trees or rocks, which are chosen by the family of the deceased, unless that choice was made by the deceased person while he or she was still alive. Those who go there to commemorate a deceased person have nothing else to do but spend time there, because they do not have to do any maintenance.

Of course, I don’t know anyone of those people whose ashes are buried in that place, but moving through that wood I felt them to be part of myself, because they are part of the universe together with me, they nourish it, they are part of the nature that creates and transforms.

Next, in the end, if dying I should find out that there is something there, I would much rather go to the woods together and meet new people, than to be locked in a marble condo squabbling over space issues, it is already too much to have to do in life!

The costs of burying ashes in the natural cemetery are relatively low, especially considering the fact that there are no maintenance costs. Fail to find any reason to practice such solutions in any municipality, whether small or large, because it is always better to provide for the need to expand green spaces rather than to concrete. Every landscape can offer different burial places without any negative implications. And finally dignity could be given to grief and a just end to life.

Andrea Pastore

Andrea Pastore agreed to lend his voice to a podcast series in which he tells about that particular research work, which I found fascinating, and which I have chosen to share with all of you so that you may, like me, find a stimulus to broaden your knowledge, reflect on your emotions, and find a reason to act on a change that is not secondary, because indistinctly it affects each of us.