Highlights, Inspirational

GLORIA STEINEM

25 March 2022

“Don’t worry about your background. Whether it’s strange or ordinary, use it, build on it.”

Gloria Marie Steinem was born on March 25, 1934, in Toledo (Ohio, USA): she is a feminist activist, politician, journalist, supporter of the women’s liberation movement (’60s-’70s), a movement that coincided with the second wave of the feminist movement in the USA.

Her life has been characterized by obstacles that have certainly made so structured her feminist background, and her activism in which private and the public have always traveled hand in hand. She had an uneven childhood marked by the tensions between her parents and her mother’s depression, but she never questioned the love she received from her family. Having lived a childhood constantly on the road with her family, she started attending school regularly at the age of 11 for the first time, and although she started reading independently at the age of 4, she realized that she had other deficiencies compared to her peers because she had not studied math, history, and other subjects regularly; also, having spent most of her time among adults, she was not used to playing the games that were usually played at school. She was very intelligent and mature and had a rather sophisticated sense of humor compared to her peers. She loved to discuss social issues, civil rights, and hardships. Her choices regarding further education say a lot about the awareness and determination that characterized her: in fact, she graduated in 1956 at Smith College – Massachusetts: Smith was founded as a liberal arts college and is distinguished by the fact that it provides a high-quality education aimed at women, to make them participate in society by developing their talents and strengths. It was the brainchild of Sophia Smith, a New England woman who received a large inheritance at the age of 65. In her will, she expressed her desire to donate the money to purchase the first land and erect the buildings of the women’s college, explicitly stating, “I hereby make the following provisions for the establishment and maintenance of an institution for the higher education of young women, with the design of providing my sex with means and facilities for education equal to those now offered in our colleges to young men.”

Gloria loved political science classes and was considered by her fellow students to be a bright and busy girl: she loved to debate late into the night and could both listen and converse. She was also a procrastinator when it came to turning in written papers and usually did so at the last minute. In the book “Ms. Gloria Steinem – A life”, Winifred Conkling quotes an anecdote about this: during her second year of college, a professor told her that she wrote “easily and well”. Gloria asked him what he meant by “easily” and he replied that if she was so paranoid as to notice the word “easily” and not the word “well”, this proved that she was a real writer.

She graduated magna cum laude and was one of the top students in her class. At the time she was engaged to Blair Chotzinoff, a National Guard pilot, and it seemed a foregone conclusion that she was destined to marry him. But although they were very close, Gloria knew that marriage would be the wrong path for her to follow. So she decided, to make the end of their relationship, which was nonetheless very passionate, less difficult, to apply for a postgraduate fellowship in India. She first had to go to London to wait for her visa: here she realized she was pregnant. She didn’t talk to anyone about it; she was certain she didn’t want to get married, didn’t want to give up her independence, and didn’t want to be responsible for someone else’s life after spending her childhood taking care of her mother. She also thought about suicide, but she didn’t want to die. She sought out a doctor, to whom she told of being abandoned by her man who refused to marry her even though he suspected she was pregnant.

In England, abortion was legal only if two doctors gave a positive opinion on the necessity of the procedure. And this was usually done with great reluctance. Gloria found the agreement of the first doctor who had examined her and found a second, so she was able to terminate the pregnancy. Of this experience, Gloria said, years later, that this was the first time in her life that she stopped passively accepting what was happening to her and took responsibility for it.

She went to India in 1957, in Delhi: she chose to live this experience without adopting the perspective of an external observer, but simply as a girl who alone was trying to fit into the normality of life in the country that was hosting her. In this way, she felt she could explore to the fullest. Periodically she had to report on her experience to the scholarship committee: she told them about the culture, the extreme poverty she encountered. He learned a lot about India’s recent history and the struggle for independence. Her scholarship had a duration of three months, but Gloria decided to stay in India: she began to travel alone, discovering the horrible caste system and meeting those who were carrying on Mahatma Gandhi’s work to erase them. The Gandhians moved from village to village to meet people and encourage them to join them, but only women could meet other women, so Gloria chose to join them to help, carrying only a towel, a cup, and a comb, discovering that there was a form of freedom in not owning anything, that this allowed her to live in the present. She discovered at this time the power of “talking circles” and the possibility for people to tell their own stories. This allowed people to discover that their experience of social injustice was common to others, that what happens to many people becomes political, no longer personal. She learned that listening creates listening and observation creates observation. Thanks to this experience, Gloria Steinem embarked on the path of activism, to produce social change from below.

In 1960, she moved to New York where she began her freelance writing career: she began by writing for the satirical magazine “Help! For Tired Minds”. , continuing with Esquire, The New York Times, Glamour, Ladie’s Home Journal, and Harper’s.

In 1963 he wrote for the magazine Show an article on the life of Playboy bunnies entitled “A Bunny’s Tale: Show’s First Exposè for Intelligent People”. : Hugh Hefner had in fact opened a new Playboy Club in New York and Gloria applied for a waitress position. In recruiting new bunnies, the Playboy organization portrayed their lives as glossy, fun, and full of financial rewards. Before long Gloria discovered that Bunny’s life was truly stressful: lots of work, not at all generous pay. They had to wear very tight costumes, padded over the breasts to show off their décolletage in an exaggerated manner, high heels, and take a make-up course before starting work, learning how to apply false eyelashes. To top it off, they had to study the Playboy Bunny Club bible and pass a medical exam that involved vaginal and blood tests to make sure they didn’t have any STDs – which weren’t required to do waitress work in New York State. By publishing this article, Gloria wanted to discourage girls from wanting to become waitresses in a Playboy, because they would become like geishas serving the benefactors of the Club. She said that this had been one of the most depressing experiences of her life. She was sued in court by Hefner, who lost the case but Gloria had to pay all her legal fees. This discouraged others from publishing articles about the working conditions in the Playboy Clubs, but Hefner removed the medical examination clause from the employment contracts.

After this article, Gloria became a sort of celebrity and was no longer considered just a writer, but on more than one occasion stressed that she did not want to be presented only as the author of that article because she had written so much more.

As the years went by, Gloria Steinem became a point of reference for many magazines. Although she was considered by many an insider, she considered herself an outsider, carrying with her vision of the world and relationships cultivated since childhood and in her life experiences. She attended social events, and took on work assignments, but always from the perspective of a freelancer: she chose when things had to end.

In the 1960s she was involved in protest movements for social justice, protesting the war in Vietnam, in favor of civil rights. She knew how to use her position, her visibility, and her relationships, to promote activism in support of all these causes.

She was very determined to be recognized as a committed and serious writer, and although she had experience and expertise, she often felt devalued especially in contexts where she intercepted male colleagues. On many occasions she had felt anger and humiliation, not knowing how to react. With time, she listened to her emotions, and her reactions, even though she believed that anger was a negative feeling that should not be expressed.

Bella Abzug

Then she met Bella Abzug: it was during a protest demonstration against the war in Vietnam, in front of the Pentagon, where photos of children after napalm bombings were shown. Bella Abzug was one of the spokeswomen for the protest – she later became a member of Congress. You only have to look for any archived video to appreciate the passion with which Bella Abzug addressed each speech, the real anger against any violation of human rights. Gloria at first considered Bella aggressive and out of place, she felt uncomfortable listening to her. She had also been offensive to some political representatives who supported the protest, although her words did not make them give up. For Gloria, it was not a pleasant experience.

Betty Friedan

The two women met later, at another protest event: Gloria began to appreciate her passion and realized that

the problem was not Bella, but her reaction to her expressing her anger. She began to realize that deep down it bothered her that Bella was a complete, angry person who could express her anger.

In 1963, Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique”, considered her seminal essay, came out, the result of interviews she had done in the 1950s across the country with white middle-class women who had found themselves in the postwar roles of wives and mothers. Among those interviewed were her former colleagues studying at Smith College. What emerged was a female condition linked to the roles covered within the relationships mainly of care – wife, mother, housewife, serving the welfare of husband and children – which left no room for individuality, aspirations, desires. Thanks to this essay, many women were prompted to reflect on their roles and became part of the feminist movement. Gloria didn’t recognize herself in this work, because she didn’t have to do with the women interviewed, with the condition that Friedan had brought out: she was an independent, unmarried woman, who worked and didn’t depend on a man. She did not consider that to be her struggle, and she questioned her membership in the feminist movement; she called herself a humanist rather than a feminist. Friedan founded, along with other women, the largest organization of feminist activists in the United States, the National Organization for Women -NOW– which Gloria did not formally join, though she supported its political agenda. She felt it was not centered enough on lesbian women’s rights, poverty, and the demands of women of color. She was invited to participate in a NOW protest in front of a Hotel where unaccompanied women were not served lunch. She decided to intervene as a reporter, not as an affiliate of the organization. She did so because sometime before she had experienced being kicked out of that Hotel while waiting for someone she was to interview, precisely because she was not accompanied by a man. The fact that she was unaccompanied suggested that she was a prostitute. That first time she was not ready with her answer, but when she came back the second time, she asked why single men, who could very well be prostitutes, were not kicked out. She realized that she was seeing the world through the feminist lens: women were judged by how they appeared in the eyes of others, how they dressed, and by how they presented themselves in public. For a long time, she had been aware of the sexism she had suffered but had accepted it as something that could not be changed.

Isn’t this wonderful?

Isn’t it wonderful to be able to confront the history of women who have so influenced our present, through the paths of self-awareness, observation, and reflection, which are not so different from our own? It gives me the shivers to meet in the biography of such extraordinary women my own doubts, my insecurities, but also my certainties, my thoughts, my history.

Every now and then we need to brush up on history to put ourselves back in the center, and throw out everything that doesn’t have to do with what makes us complete people. I would shout it out loud to the people who have consciously wanted to tear down my dignity, but it is not worth wasting breath with the past when we have stories of extraordinary activism to exhort us!

In 1968 Gloria began writing for New York Magazine’s “The City Politic” column. It was a time when there was a lot to write about, from the Vietnam War to civil rights, from political campaigns to the assassination of Martin Luther King and the ensuing riots. She was there to write an article, but she couldn’t not feel involved because of her abortion experience, and in 1969 she attended the feminist group Redstockings meeting on the topic of abortion, during which women told their own abortion’s experiences, keeping in mind that it was an illegal practice in the United States. She was there to write an article, but she couldn’t not feel involved because of her own abortion experience, which she had been able to live through legally. She was also impressed by all of those women’s capacity to share their lives openly. This was how Gloria became aware of feminist activism: women’s rights were tied to civil rights, and they were mutually reinforcing.

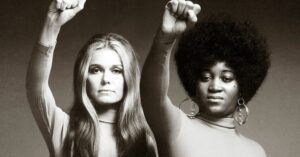

Gloria and Dorothy Pitman-Hughes

Obviously, when she dedicated herself to studying and writing about feminist issues, she received a lot of criticism from writers and editors who blamed her for dedicating herself to non-directive issues and damaging her career. In her life, she had always preferred to write rather than intervene in television debates and in general speak in public, but through the attendance of feminist groups, she discovered that she found this practice less annoying when she was together with other women, and she discovered it thanks to the meeting first with Dorothy Pitman Hughes and later with Florynce “Flo” Kennedy.

Gloria and Flo Kennedy

We have read many times among the slogans of feminist protests the phrase “If men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament!”: this quote was pronounced by a taxi driver who was taking Gloria and Florynce to Boston and had heard their discussion on abortion. By dint of quoting this expression, it became one of the iconic phrases of the movement. Over the years, the practice of conversation, confrontation, and exchange became privileged for Gloria over the one-way communication of writing. Again, change came through her direct experience, and her ability to question what she took for granted.

It’s these experiences, my own life, that I think of when someone tells me “people don’t change because you can’t change the personality, the attitudes either. You can’t expect someone to change the way they see things.”: who says that? Do we have unchanging default settings? So what is the purpose of life if not to have experiences that bring change within and without? If we were not able to produce change through experience, we would still be living in caves, we would not be able to acquire skills, and it would be completely useless to be in a relationship. It’s simple reasoning, but in practice it challenges certainties, it opens a hole in the fence we have built. I find it extraordinary to be able to get out of that fence, I don’t understand how you can want to stay inside it for the rest of your life. Change is a free and conscious choice.

Gloria was becoming a celebrity, although she had no such ambition. But her notoriety allowed her to give visibility to the demands of the feminist movement.

To understand her notoriety, and the consideration that women who opposed the feminist movement had of her, it is useful to consider the events related to the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) that was proposed – and rejected by Congress – every year since 1923 and had the purpose of strengthening equal rights regardless of gender. In this scenario comes into play a woman who is considered one of Gloria’s greatest antagonists, Phyllis Stewart Schlafly, who ran with the Republicans in 1952 for the House of Representatives in a constituency with a Democratic majority.

Phyllis Schlafly

She was not successful but continued with her political commitment. In 1964 she published a book “A choice, not an echo” through which she influenced the conservative push within the Republican Party that stopped the approval of the Equal Rights Amendment of which Schlafly was one of the most ardent opponents: The TV series Mrs. America perfectly renders her image as that of a woman herself trapped in the contradictions of patriarchy, but who manages to get the attention of the male establishment through the actions related to the campaign against the ERA: perfectly in coherence with the communicative strategies of conservative forces opposed to the recognition of human and civil rights, manipulates the contents of the amendment, going to solicit stereotypes and prejudices related to feminism, and instilling the doubt that the recognition of equal rights leads to the demolition of privileges and catastrophic prospects to the detriment of the “good society”. To emphasize the differences in being in the relation between the two different groups of women – feminists and conservatives: the former acting out internal conflicts, dealing with internal differences, building shared leadership and practicing critique, not hiding their anger and nature; the latter imposing leadership through manipulation, false flattery to create consensus, caring about appearing rather than being through meticulous care of appearance and manners, attacking opponents on a personal rather than political level, reproducing male power dynamics. Does this resonate with you? This is a series that absolutely must be seen, also to get to know Gloria Steinem’s story through her battles, the conflicts within the movement, the everydayness of her life, and thoughts that I have tried to summarize in this piece, as well as the tensions with Betty Friedan.

So many women on different sides, housing us in the era of the second-wave feminist movement and allowing us to draw parallels with the era we are living in, making it clear why we need to continually look back to move forward.

Above all, continually referencing Gloria Steinem’s biography, inevitably immerses us in her personal-political, and some of us will come to think we were born in the wrong era. But let’s not forget that the feminist movement is still a global movement, constantly moving like a wave across the world, driven by the spirit of sisterhood that brought the voices of women who fought so that we can fight so that we can recognize ourselves wherever we go.

In 1971 there were no women Supreme Court Justices or Governors in the United States, women could not change laws unless they were legislators, and the possibility of women being represented in government was very remote. Gloria, along with Betty Friedan, Congresswomen Bella Abzug

and Shirley Chisholm (the first black woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives), who were joined by other women, founded the National Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC), which represented both Democratic and Republican women, white and black, rich and poor: in short, so many differences that necessarily to effect change it was necessary to find compromises and common purpose

Simultaneously, Gloria began working on the idea of founding a magazine that would deal with contemporary issues from a feminist perspective: thus was born Ms. Magazine, which took its first steps through the publication of an insert in New York Magazine, in December 1971.

Angela Davis

In 1972, the magazine’s first stand-alone issue came out. It was the first feminist magazine in the United States, and the first to publish on its cover, 1976, the theme of domestic violence. That same year, Angela Davis‘ analysis of the intersection of gender, race, and social class was published, starting with the case of an African American woman accused of killing the white prison guard who had sexually assaulted her. Ms. Magazine is still today a stimulating and engaging source of feminist knowledge that manages to inform and educate, promoting activism on a global level, with the collaboration of scholars, experts, organizations, and students who can find unique material for study and insight. Gloria Steinem has been able to synthesize her experience and make it available to everyone.

In 1986 “Marilyn: Norma Jean” was published, Gloria Steinem’s portrait of the most beloved sex symbol of all time, through an interview she had given to photographer George Barris shortly before her death: whoever had written about Marilyn had ignored Norma Jean, her complex life made up of abuse and trauma, her intelligence and her depth. In that same year, Gloria discovered she had breast cancer. The surgical and healing process stimulated a new change in her: she began to think about her health, listen to her body’s warnings, and take care of those close to her affected by cancer.

After going through some economic difficulties in Ms. Magazine, in the nineties, Gloria decided to take care of herself as much as other people and movement, through a slower, healthier lifestyle, and explore her life through therapy. The result of her new revolution was the publication of “Revolution from Within: A Book of Self-Esteem” in which, through her own life experience and that of other people, she conveys the need to go through a journey of self-awareness and self-knowledge to enact an inner revolution that precedes any outer revolution. As she worked on writing this book, she realized that “we teach what we need to learn, and we write what we need to know.”

Gloria faced the passing years with great awareness, curiosity, and constant change, taking nothing for granted or unchanging. In fact, at the age of sixty-six, in 2000, she married David Bale, a South African-born anti-apartheid and animal rights activist, businessman, and father of four adult children. The movement’s struggles had made egalitarian marriage possible, and to those who asked her how she reconciled marriage with feminist activism, she replied that being a feminist has to do with being able to decide what is best for our lives every time. Davida Bale died in 2003 of cancer, Gloria cared for him throughout his illness and realized that caring for an adult as an adult is very different from caring for an adult as a child, as she had done with her mother.

In 2005 she and Jane Fonda founded the Women’s Media Center, to make women more visible and powerful in the media.

On March 25, 2022, Gloria Steinem turned 88 years old, and she never stopped her revolution, she never stopped supporting the feminist movement and women’s empowerment, she never considered herself a beacon for the movement, because every woman is from herself. Every one of her birthdays becomes an opportunity to raise money and so she has decided that it will be her funeral. Her home will become a meeting and organizing place for feminists because.

“A mutual understanding comes from being together in a room.”